- Home

- Pseudonymous Bosch

Write This Book: A Do-It-Yourself Mystery Page 2

Write This Book: A Do-It-Yourself Mystery Read online

Page 2

The French have a name for this practice of preassembling ingredients, as they do for many crucial culinary activities: the mise en place. The set in place. To make sure you have all the materials you need for your book, I suggest you create a literary mise en place.

What should go into your mise en place? Aside from those chocolate chips, of course. (Chocolate, I’m sure you’ll agree, is absolutely vital to the writing process.) Well, what is necessary for writing? Let’s start with the basics:

• a writing utensil (pen, pencil, crayon, feather quill, electronic computational device, lipstick, chocolate-smeared finger)

• a writing surface (napkin, table, tablet, chalkboard, bedroom wall, dusty car window, plaster cast, old tennis shoe, palm of hand)

• and… something to write about (Ah, now that’s the tricky one, isn’t it?)

What should you keep by your side to help you come up with story ideas? One answer is: anything that inspires you.

Feel free to ignore this list and create your own:

A BAD DREAM

A GOOD JOKE

AN OLD COMIC

A BROKEN TOY

AN OVERHEARD CONVERSATION

CHOCOLATE

MORE CHOCOLATE

RANDOM FACTS ABOUT BLACK HOLES AND DINOSAURS

A PICTURE OF YOUR ENEMY WITH A SCRIBBLE MUSTACHE

A PAGE COPIED FROM YOUR SISTER’S DIARY

YOUR FATHER’S HAT

YOUR FAVORITE SHOE

A LIST OF FUNNY FOREIGN SWEAR WORDS

A UFO SIGHTING

A REFLECTIVE SURFACE

A DIAGRAM OF A SPACE STATION… FOR MICE

AND DID I MENTION CHOCOLATE?

But if the story you’re telling is not utterly unconventional—if it’s not just a bunch of unrelated words strung together—then your story probably consists of somebody doing something… somewhere. Right? Thus, in addition to all the delightfully strange things your imagination can come up with, your mise en place should probably include:

• a hero (such as a knight or a wizard or a collie)

• a task for said hero to perform (in most cases, this task will not be easy; it will entail overcoming obstacles—befriending dragons, fighting inner demons, learning to spell Azerbaijan—to achieve a goal)

• and a world in which said hero performs said task (also known as the setting of the story)

Those three things are the main elements of most stories. Obvious? Perhaps. But it took me years to learn this simple formula—or maybe, in keeping with the mise en place idea, I should say this simple recipe.*

Take my favorite book of all time, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. The hero of the book? Easy. It’s Charlie, the poor boy who doesn’t have enough to eat. The world of the book? Also easy. Willy Wonka’s magical and mysterious chocolate factory—it’s right there in the title alongside the name of our hero. Our hero’s task? Well, I suppose that one’s a little more difficult to discern. In the early part of the book, Charlie’s task is to find a golden ticket so as to gain entry to the chocolate factory and earn a lifetime’s supply of chocolate. Later, it turns out that he has been unknowingly performing a much larger task: proving his moral worth to Wonka, thereby making himself Wonka’s heir and ensuring that he will have not just a lifetime’s but an absolutely unlimited supply of chocolate. Thus, you might say, Charlie’s real task is to acquire as much chocolate as humanly possible—a task I set for myself every day.

Now let’s get back to your story.

I have already (and very helpfully, I might add!) supplied a task for your hero to perform: finding the missing author—that mysteriously familiar-sounding mystery novelist, I.B. Anonymous. The world of your book is the time and place in which I.B. must be found; and we’ll get there soon enough—i.e., at another time and place. Which leaves your hero—him-, her-, or itself—the most important element of a story, according to many writers wiser than I. (Me, I tend to judge books by the number of references to chocolate; you’ll notice I try to write the word as often as possible.)

So, my budding young author friend, who is your protagonist, as your language arts teacher might put it?

Who is the hero of your book?

Pseudo-intelligence: To outline or not to outline?

A mise en place is not to be confused with that dread thing—I hesitate even to mention the word—an outline. If you like outlines—and many do, especially editors and teachers and other people I consider my natural enemies—then great, go to it, outline away. Bullet points. Index cards. Spreadsheets. They’re all yours. To me, outlines are worse than unhelpful—they’re totally disheartening—for the simple reason that I am never able to complete them. Instead of giving me confidence in the book I’m writing, an outline makes me all too aware of how difficult it’s going to be to get to the end. What I like about the idea of the mise en place is that it allows you to gather story elements without forcing you to think through your entire novel before it’s written. A mise en place implies a recipe—but an open-ended one. A recipe that’s subject to change.

Your Heroes: From A to Z

I say heroes—plural—because, as you no doubt have noted, I’ve already given you two: the siblings A____ and Z____. Why? With two heroes, there are more opportunities to write dialogue; and, as everyone knows, dialogue is much more fun to read than description. Also, having two heroes allows us to make one a girl and one a boy. That way all your readers will feel represented.

For simplicity’s sake, I made A____ and Z____ sister and brother. But you can change most everything about them, including their relationship. Perhaps they’re not a girl and a boy after all. Perhaps they’re a girl and her pet monster. Or, better yet, a monster and his pet girl.

The one thing you cannot change is the role they play. If they are your heroes, then they are the ones who must track down the missing author. As you create their characters in your imagination, you should think about what kind of people would be best suited for this role—and what kind least suited. (Sometimes, it’s more fun to have an unlikely hero.) From the prologue, we can surmise that A____ and Z____ are curious about their neighbor. Are they reluctant detectives or eager ones? Perhaps they’re aspiring authors themselves? You decide.

What matters is that they are actively engaged with their quest and that you, their author, are actively engaged with them.

Pseudo-intelligence: Is this book a girl book or a boy book?

Few questions irk me more than that one. Memo to parents, children, Santa Claus, and all interested parties: a book does not have a gender. Whether it’s pink and sparkly and wearing a tutu, or covered with grass stains and wearing a baseball cap, a book is a book is a book, and anybody can read it, boy, girl, or chimpanzee! And, for the record, my feelings about this question have nothing—absolutely nothing—to do with my own boyhood reading choices. Little House on the Prairie? Never heard of it. Nancy Drew? More like Nancy Who? You must have me confused with somebody else. I myself was reading, er, something else. OK, fine, it was Little Women. So what…

SIGNATURE PRACTICE

A famous author has to sign her name over and over. True, not every author is going to become famous, but it doesn’t hurt to practice. Use this space to perfect your autograph. You will have to learn to write fast if you want to sign hundreds of books at a time, but try not to sacrifice style for speed. A little flourish in that signature, please.

Famously yours,

You’re my sister? I’m sorry, I don’t remember you.

All it takes is a little luck… and a lot of talent.

What, this old book? I wrote it years ago.

I never forget the little people—

I just don’t talk to them anymore.

By the way, I also star in movies.

Enough dillydallying. It’s time for you to get back to work. And I mean it this time!

(See how tough I can be when I want to be? Unfortunately, the toughness never works when I try it on myself.)

&nbs

p; Start with your heroes’ names. Presumably, A and Z are their initials, but they don’t have to be. In fact, I picked the letters to suggest that the names could be anything you like—any names from A to Z. Get it? Just keep in mind that names have power; sometimes a name alone is enough to create a character.

Please enter your heroes’ full names here.

A____’s full name:

Z____’s full name:

Pseudo-intelligence: The name game

There are as many ways to name a character as there are to name a baby or a newly discovered insect species.

Some authors choose names that express something unique about their character. This might be a color or animal or flower, like Blue or Wolf or Iris. Another author might adopt the name of a favorite pet or the name of a hated PE teacher or the name of a certain teenage singer famous for his dirty-blond bangs. As you may remember, my Secret Series character Max-Ernest has two names because his parents couldn’t agree on just one, but there is a secret reason I gave him those two particular names (or pseudonyms, I should say, since his real names are something else entirely). Although he wants desperately to be funny, Max-Ernest can’t help being serious—that is, earnest. Maximally so. He is earnest to the max. Hence Max-Ernest.*

Other authors think names needn’t be so meaningful (or silly); instead, they should be as realistic as possible. Or realistic for the worlds they are portraying. A name that sounds realistic in Maine might not sound realistic on Mars. Isabel Robbins, for example, just doesn’t say Martian to me. Izzi, on the other hand, has major Martian potential….

If you have trouble picking a name, do what I do when I’m stuck: choose a book at random—dictionaries are great—open to the middle, and use the first name you find. Phalanger…? Phalanstery…? Phalanx…? Let’s try again. Truncheon… Trundle… Trunk… Well, you get the idea….

Now that you’ve named your heroes—if you don’t mind, I’ll still refer to them as A____ and Z____—I think it would be a good idea to jot down some notes about their personalities and appearance and so on.*

On here–here, you will find a very official-looking character assessment form to fill out. (In reality, there’s nothing official about it; I just made it up.) Think of the form as a longer version of one of those irritating little personality quizzes that other kids send around via e-mail. (You never send them, I’m sure.) Or else pretend you’re choosing attributes for your personal avatar in some virtual world or video game where the goal isn’t to win but rather to be as fascinating as possible.

If you get stuck, try answering the questions for yourself; how would you describe you? There’s no reason you can’t model one of your characters on yourself. Or on anybody else you know, for that matter. Just make sure you change enough details to allow for plausible deniability. (That stubborn, pointy-eared troublemaker? Why on earth would you think I based her on you? Your ears aren’t that big. True, they stick out a bit, but…) You don’t want anybody hunting you down in a murderous rage after reading your book.

Pseudo-intelligence: Is your book autobiographical?

Readers often ask authors if their characters are based on themselves. And almost always, the answer is: yes and no. Sometimes our characters represent the people we wish we were; sometimes they represent the people we fear we might be; and sometimes our characters reveal things about us we never knew. Whatever your intention, my guess is your characters will wind up resembling you in ways you don’t expect. Books can be quite scary that way.

NAME:

CODE NAME OR PSEUDONYM (a must for any self-respecting character!):

SPECIES (real or invented):

AGE (in human years unless otherwise specified):

HAIR COLOR (unless bald… or furry):

EYE COLOR (or colors, if multiple):

UNDERWEAR COLOR (You should know your characters from top to bottom!):

UNIFORM (cape and tights, shining armor, mascot-style bear suit):

OTHER DISTINGUISHING PHYSICAL FEATURES (missing limbs, extra fingers, green skin, a gaseous being with no body):

PERSONALITY (cautious or impulsive? studious or adventurous? calm or hyperactive? funny or glum?):

HOBBIES, INTERESTS, TALENTS (reads minds, charms snakes, swallows swords):

EATING HABITS (vegan, eats with mouth open, only eats purple foods):

PICKS NOSE? Y/N (I just threw this one in—you don’t have to answer if you’re too squeamish.)

CATCHPHRASE (Every hero has to have one!):

VERBAL TIC (stutters, says um and like a lot, sing-song voice):

THEME SONG:

SUPERPOWER (and don’t say superstrong—that’s a cop-out):

GREATEST DESIRE (whether publicly acknowledged or secret):

GREATEST FEAR (clowns, mayonnaise, anything—but choose carefully; this one might come back to bite you, as it were):

FATAL FLAW (pride, greed, jealousy, addiction to a certain type of sweets—your hero’s fatal flaw is what will bring him down, and what he will have to overcome before your story is over):

Terrific! Great job! I can see you’re an expert, er, characterizer! You’re on your way to writing a heckuva novel!*

In all seriousness, keep those character profiles handy, not just to help you describe your characters but also to help you plot your story. Your heroes’ personalities will help determine the choices they make and thus the course your story takes. Of course, the reverse is also true; you may find your understanding of a character changes as your story progresses. Characters are just like people; no matter how well you think you know them, they always surprise you.

Pseudo-assignment: Voice mail

Now that you know your heroes, write voice mail messages for them. No Hello, you have reached so-and-so.… Try to be more creative. Are your heroes the type of people to use a song as a greeting? Or are they more likely to greet callers with a recording of a barking dog? Maybe they don’t use phones at all but rather communicate through owl or carrier pigeon. Mental telepathy? (What would telepathic voice mail sound like?) Don’t forget to include a few voice mail messages or texts that your heroes are likely to receive in return. Who are your heroes’ friends? What kinds of things are going on in your heroes’ lives that might appear in phone messages? For extra credit, record one of your heroes’ fictional greetings on your own voice mail and confuse all the real people who call you.

RANDOM WRITING TIP: BRAINSTORMS

Never let yourself get caught unprepared in a brainstorm.

Many writers will tell you always to carry a notepad and pen so that you can jot down any and all ideas that happen to fall from the sky. Myself, I only carry a pen. I find that the palm of my hand is a much better writing surface than a notepad when it’s raining.

AKA Chapter 1

So, my dear author, getting back to your book, how do you think you should begin your first chapter? The next day seems like the most natural place to start, does it not?

Unless you have a better idea, you should probably begin with A____ and/or Z____ waking up.

Use this moment to establish the personalities that you so carefully analyzed earlier. What do their bedrooms look like? Do they jump out of bed or linger under the covers? Do they pick up rumpled clothes from the floor or take a neatly folded shirt out of a drawer? How do they brush their teeth? Or don’t they? Do they have any funny or weird morning rituals they wouldn’t want anybody to see? Remember, you want your reader to love your heroes enough to spend an entire book with them—but that doesn’t mean your reader has to like everything about them.

WRITE THIS:

Describe A____ or Z____ or both as they wake up in the morning. As you write, to maintain dramatic tension, make reference to the frightening sounds Z____ heard the previous night.* Do A____ and Z____ wake up thinking about all the horrible things that might have happened? If you need more space, attach an extra page. Or just write over my words. I don’t need them. And don’t forget to title your chapter—whether at the

beginning or the end.**

The Case of the Missing Author

Chapter 1

INSERT CHAPTER TITLE HERE

In which A____ and Z____ wake up and demonstrate winning character traits that make your reader want to read a whole book about them.

Good. Now we know that your heroes didn’t die overnight—always an important fact to establish. But did their neighbor die overnight? That’s the question your readers will be—

Oh, no. I just had a terrible thought. Before we get to all that fun mystery stuff inside I.B.’s house, we have some ugly writing business to attend to:

PARENTS!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!*

There’s no way around it: they have to be part of this chapter.

You know what they say: Parents—can’t live with ’em, can’t live without ’em. Parents, as any writer of books for young people will tell you, are the worst. They’re always getting in the way, making your heroes eat breakfast or do their homework or wash dishes—anything to keep them from going off on an adventure. Parents can stop a good book in its tracks. In that sense, a book is much like life.

You Have to Stop This

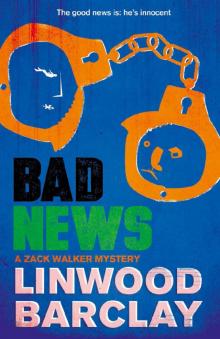

You Have to Stop This Bad News

Bad News Write This Book: A Do-It-Yourself Mystery

Write This Book: A Do-It-Yourself Mystery Bad Magic

Bad Magic If You're Reading This, It's Too Late

If You're Reading This, It's Too Late This Isn't What It Looks Like

This Isn't What It Looks Like Bad Luck

Bad Luck The Name of This Book Is Secret

The Name of This Book Is Secret The Unbelievable Oliver and the Sawed-in-Half Dads

The Unbelievable Oliver and the Sawed-in-Half Dads The Unbelievable Oliver and the Four Jokers

The Unbelievable Oliver and the Four Jokers This Book Is Not Good for You

This Book Is Not Good for You This Isn't What It Looks Like-secret 4

This Isn't What It Looks Like-secret 4 Write This Book: A Do-It-Yourself Mystery (The Secret Series)

Write This Book: A Do-It-Yourself Mystery (The Secret Series)