- Home

- Pseudonymous Bosch

This Isn't What It Looks Like

This Isn't What It Looks Like Read online

Copyright

Copyright © 2010 by Pseudonymous Bosch

Illustrations copyright © 2010 by Gilbert Ford

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at www.HachetteBookGroup.com.

www.lb-kids.com.

Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

First eBook Edition: September 2010

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author. Then again, he never intended to write this book in the first place.

ISBN: 978-0-316-12207-8

FOR

SOFIA CAROLINA (SO NICE, THEY NAMED HER TWICE); IZZY AND JACK; ELIJAH; ISABELLA; KATE P. AND EMMA (EVEN IF SHE’S TOO OLD) BUT NOT MAY AGAIN (WOULDN’T BE FAIR); KATE G. AND SAM; ELLA AND MARGAUX; LILY WITH A Y, GIDEON, AND RUFUS; BUT NOT LILLI WITH AN I OR LUCAS OR MADELEINE (SEE BOOK TWO); AND NOT INDIA AND NATALIA, EITHER (WELL, MAYBE WE’LL LEAVE THAT OPEN FOR DISCUSSION); ALSO FOR AVA AND SYLVIE; LUCY AND LEVI; DULCE AND OLIVIA; TYLER X 2; IRIS; STASH; LORENZA; THE LOCAL COUSINS: LEV, DANTE, AND MOLLY; THE NORTHERN COUSINS: NAOMI, ELI, AND JACOB; THE MYSTERIOUS COUSIN, SOPHIA; AND FINALLY FOR NABU AND KIWI SKUNK AND MY “MOST ANNOYING FAN EVER” AND MY SECRET AGENT IN KENTUCKY AND ALL MY SECRET AGENTS EVERYWHERE

Contents

Copyright

WARNINGS, DISCLAIMERS, FINE PRINT & ETC.

PSEUDO-MANIFESTO

AUTHOR’S NOTE

CHAPTER-TEN: Goat! Goat!

CHAPTER ONE: A Deep Sleep

CHAPTER-NINE: The Seer

CHAPTER TWO: Tarocchino

CHAPTER-EIGHT: Double Vision

CHAPTER THREE: Magnets

CHAPTER-SEVEN: Dogs Not Hogs

CHAPTER FOUR: New Kid Old Comrade

CHAPTER-SIX: The Royal Kennels

CHAPTER FIVE: An Important Announcement

CHAPTER-FIVE: A Conversation in the Dark

CHAPTER SIX: Back to School

CHAPTER-FOUR: Anastasid

CHAPTER SEVEN: The Mopping Hour

CHAPTER EIGHT: Heist

CHAPTER NINE: Oh No! The Baby’s in the Mayo!

CHAPTER-THREE: Surrounded!

CHAPTER TEN: The Mole, The Monocle, and The Mole

CHAPTER-TWO: An Old Legend in Reverse

CHAPTER ELEVEN: The Man in the Mirror

CHAPTER-ONE: Portbait of An Invisible Girl

CHAPTER TWELVE: Here Goes Nothing

CHAPTER ZERO: Intermission

CHAPTER THIRTEEN: An Extra-Extra-Long Guitar Solo

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN: The Glob Blog

CHAPTER SIXTEEN: Hats

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN: Seeing Things

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN: The Joust

CHAPTER NINETEEN: Opal, Like the Rock

CHAPTER TWENTY: As Above, So Below

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE: The Lodestone

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO: The Trunk

APPENDICES

WARNINGS,

DISCLAIMERS,

FINE PRINT & ETC.

Do not read this book standing up. You may fall down from shock. • Do not read this book sitting down. A quick escape may be necessary. • Operating a moving vehicle or any kind of heavy machinery while reading this book is forbidden. It might distract you from the plot. • Prolonged exposure to this book may cause dizziness and, in extreme cases, paranoid delusions or even psychosis. If that is your idea of fun, by all means keep reading. If it’s not, then this isn’t your kind of book. • Use of this book for other than the intended purpose is not advised. While it may seem like an ideal projectile, the makers of this book cannot guarantee your safety if you throw it at someone. There is always the possibility that that person will throw it back. • You should not read this book if the cover has been tampered with or removed. If you suspect that your book has been deliberately altered by your enemies, you should report it to the makers of this book. However, they will probably think you are crazy. Under no circumstances should you consult a doctor. He will definitely think you are crazy. • The contents of this book may appear to have shifted over time. Do not be alarmed. This is a natural occurrence that affects all books and does not necessarily mean that your book has rewritten itself. Then again, it might have. • Remember, nothing in this book is what it looks like.

PSEUDO-MANIFESTO*

1. Truth is only stranger than fiction if you’re a stranger to the truth. Which means you’re either a liar or you’re fictional.

2. A realistic story is a story lacking in imagination. (What does realistic mean, anyway? Would you say something is true-istic?)

3. I’ve never met a joke so bad I didn’t like it. Then again, I’ve never met a joke.

4. When in doubt, you can’t be wrong.

5. Whether it’s chocolate or socks, the rule is the same: the darker the better.

6. There is more to life than chocolate. There is, for example, cheese.

7. If a waiter accidentally serves you a burger with mayonnaise, it’s not enough for him to scrape it off. He must order you a new burger.

8. It’s pronounced sue DON im us.

9. Secret? What Secret?

10. I know you are, but what am I?

AUTHOR’S NOTE:

AT A CERTAIN POINT IN THE FIRST 150 PAGES OF THIS BOOK THERE WILL BE AN EMERGENCY DRILL. PLEASE FOLLOW ALL INSTRUCTIONS AND BEHAVE EXACTLY AS YOU WOULD IN A REAL EMERGENCY. THANK YOU.

P.B.

*AS YOU WILL DISCOVER, I HAVE NUMBERED THIS AND SEVERAL OTHER CHAPTERS NEGATIVELY, SO TO SPEAK. ALAS, I CANNOT TELL YOU WHY WITHOUT GIVING AWAY TOO MUCH. BUT IF YOU HAVE STUDIED INTEGERS, YOU MAY WELL BE ABLE TO GUESS. YOU KNOW, FOR EXAMPLE, THAT A NEGATIVE NUMBER IS A NUMBER WHOSE VALUE IS LESS THAN ZERO, AND THAT THE “HIGHER” THE NEGATIVE NUMBER IS, THE LOWER ITS VALUE. THUS, WHEN YOU ORDER TWO NEGATIVE NUMBERS IN SEQUENCE, THE HIGHER OF THE TWO ALWAYS COMES BEFORE (HINT, HINT) THE LOWER. NEGATIVE TEN COMES BEFORE NEGATIVE NINE, AND SO ON, UNTIL YOU GET TO ZERO AND THINGS TURN NORMAL—MORE OR LESS.

How shall I put this? I must choose my words carefully.

(I know how you are. Always ready to jump on my mistakes.)

Somewhere, at some time, a girl walked down a road.

I say somewhere not because the where is secret, although it is.

I say some time not because the when is secret, although it is.

And I say a girl not because her name is secret, although it is.

No, I use these words because the girl herself did not know where she was.

Or when.

Or who.

She had woken standing up. With her eyes open.

It was a very strange sensation. Like materializing out of nowhere.

Her fingers and toes tingled. The tips of her ears burned (whether from heat or cold she wouldn’t have been able to say).

Sunspots lingered in her eyes, blurring her vision. But when she looked up she saw there was no sun. The sky was cloudy.

Had she fainted? Did she have a concussion? (She knew that confusion and blurred vision were symptoms of concussion, but she couldn’t remember how she knew it.) She touched her head, but she found no injury.

Gradually, the sunspots disappeared a

nd her vision cleared. She looked around.

She had no idea where she was.

She seemed to be in the countryside, but of what country wasn’t immediately apparent. There were fields to either side of her, but they were dry and empty. Trees dotted the landscape but in no obvious pattern. There were no signs of life.

Be systematic, she told herself. If you retrace your steps, you’ll figure out where you are.

But she couldn’t remember a thing that had happened before she was where she was. It was as if she had been born a moment ago.

Who am I…?

The realization that she didn’t know her own name came over her belatedly, like a chill you don’t notice until you see your breath clouding in the air.

She felt uneasy but not exactly frightened. Real amnesia, she knew (although she couldn’t remember how she knew it), was exceedingly rare. Most likely, her memory would return in a moment.

She decided the best thing was to walk.

The walking was not easy. There were no signs or streetlights to guide the way. The road was not paved, and it was riddled with rocks and tree roots and mud holes.

She stumbled more than once, but she trudged forward. What else was there to do?

An hour passed. Or maybe two. Or was it less?

She didn’t see anyone else. Until she did.

Ahead of her, just a few feet off the road, a little boy was climbing a big tree. Like a cat, he made his way on all fours out onto a long branch. Like a cat, he got stuck.

“Father… Father!”

His cries grew louder, but nobody came.

I wonder if he’ll recognize me, the girl thought. He could be my little brother for all I know.

“Don’t worry, I’ll get you down!” she shouted.

If the boy heard her, he showed no sign. “Father!” he kept yelling.

An old hemp rope lay beneath the tree. The remains of a swing. The girl picked it up, then automatically started to climb the old and twisting tree trunk. As if it were the natural thing to do. As if she had rescued many other children before.

Remember the Three-Point Rule, she told herself. But she couldn’t remember how she knew the rule.*

“You shouldn’t climb up trees if you’re too scared to climb down,” she said when she came close to the boy.

He ignored her, continuing to yell for his father. It certainly didn’t seem as though he recognized her.

“Are you deaf? I’m trying to help….”

The boy’s shirt—little more than a rag—had caught on a branch. As soon as the girl started to untangle him, the boy jumped in fright—and almost fell out of the tree.

She gripped him tight. “Careful—”

He screamed, “Goat! Goat!”

At least that’s what it sounded like.

“Calm down—you’re OK.”

She gave him a pat of reassurance, but his cries only grew louder and more hysterical.

“I’ll get you down, no problem.”

Expertly, she tied the rope to the tree. A Buntline Hitch Knot, she remembered the knot was called. But she didn’t remember how she knew the name.

She tugged on the boy’s shirt collar. He clung to the tree branch, refusing to move.

“Goat! Goat!”

“Is there a goat down there? Is that what’s scaring you? Don’t worry, it won’t hurt you. Goats don’t eat people. Tin cans, tennis balls, maybe—but not little boys. Not usually, anyways.” She smiled to show she was joking, but he didn’t smile back.

Eventually, she coaxed him down by gently placing his hands on the rope—then forcibly pushing him off the branch.

“Pretend it’s a fire pole!” she called after him.

He slid down the rope, a look of terror on his face.

As soon as his feet hit the ground, the boy bolted.

“You’re welcome,” said the girl under her breath.

In the distance, a man—presumably the boy’s father—waited. He wore a plumed hat, dark vest, and big, billowing sleeves. He looked like a musketeer.

He must be an actor, thought the girl. Maybe there is a theater nearby.

The boy was still crying about the goat as he jumped into his father’s arms.

The girl waved. But the man didn’t acknowledge her.

Gee, people are really friendly around here, thought the girl.

Shaking her head, she returned to the road—and stepped right into a puddle.

She grunted in annoyance.

As she shook water off her foot, she looked curiously at the puddle. The muddy water reflected blue sky and silver clouds and a flock of birds passing by.

But there was one reflection she could not see: her own.

Not goat, she thought.

Ghost.

Max-Ernest arrived at the hospital at exactly 7:59 p.m.

A nurse waved cheerily from behind the front desk. “Hi, Max-Ernest! Just in time, as usual.”

Visiting hours ended at eight. If he got there any later, he wouldn’t be let in since he wasn’t part of the patient’s family. At least not the way the hospital defined it.

Max-Ernest waved back halfheartedly.

“C’mon, honey—let’s see you turn that frown upside down. Don’t forget—”

The nurse pointed over her shoulder to a poster of a puppy wearing a red clown nose. LAUGHTER IS THE BEST MEDICINE!

Max-Ernest gritted his teeth and forced himself to smile.

That doesn’t make any sense, he almost said. How can laughter always be the best medicine? What if there’s a medicine that would save your life—like penicillin? Wouldn’t that be the best? And what if you have a broken rib? Or lung cancer? Or asthma? Laughter would make it worse, not better. And whose laughter are we talking about, anyway? Your own or somebody else’s? What if somebody is laughing at you instead of with you—is it still medicine then?* How ’bout that? Oh, and by the way, dogs don’t laugh. Some scientists think that gorillas and chimpanzees laugh. But not dogs. Not even puppies with clown noses…!

But, and this will surprise you if you know anything about him, Max-Ernest didn’t say a word. He just kept gritting his teeth and headed for the third elevator on the right.

The one marked PICU.

Every time Max-Ernest saw those four letters, he made up new meanings for them… Primates Invade Curious Universe… Penguins, Icelandic, Carry Umbrellas… Pick Icky Cuticle Up… Purple Insect Crawls Underground… Principals In Colorful Underwear… People I Can’t Understand… and so on. But the word-play was simply an old habit, a mental tic, rather than a way of amusing himself. Not even the thought of principals in colorful underwear could make him laugh now, whether laughter was the best medicine or not.

He knew too well what the letters stood for.

PICU: Pediatric Intensive Care Unit.

Perhaps the least funny place on the planet.

Max-Ernest had a lot of experience with hospitals.

His childhood had been one long battery of medical tests. Skin tests. Bone tests. Eye tests. Hearing tests. DNA tests. IQ tests. (Too much ability, they said, is a disability.) Rorschach tests. Psychological evaluations. Neurological evaluations. Cardiological evaluations. X-rays and CAT scans. They’d tested all his reflexes and tested him for all the complexes. They’d watched him eat and listened to him sleep. They’d measured his dexterity and quantified his creativity. He’d given blood samples and urine samples and even once (though he’d like to forget it) a stool sample.*

That Max-Ernest had a condition, everybody was certain; but what the condition was, nobody knew. The only thing the experts agreed on was that the main symptom was his ceaseless talking. Of course, it didn’t take an expert to tell you that.

A funny thing had happened recently, however. Funny weird, that is. Not funny funny.*

Max-Ernest, the talker, had stopped talking. Not entirely. But almost. Most of the words he uttered now were single syllables—like yes or no—and they came out in little grunts, hardly recognizabl

e as language.

It wasn’t so much that he couldn’t talk. There were still plenty of words in his head, and he could still push air out of his lungs and move his lips and tongue. It was just that talking had become a tremendous effort. Even more of an effort than it used to be for him not to talk. Words used to come out of his mouth in a nonstop torrent; shutting them off was like trying to dam a river. Now, suddenly, the river had switched direction, and talking was like trying to swim upstream when it was all he could do to swim in place.

This new condition, this unwilled silence, had fallen over him ten days ago. The day Cass had gone into the hospital. The day she had fallen into a coma.

“Not a coma like you’re thinking,” the doctor had hastily explained when she saw Cass’s mother react to the news, almost falling into a coma herself. “Not a coma like you see in the movies. Cass’s brain is very active. And she seems to be going in and out of REM cycles. She’s simply… asleep. In all likelihood, she’ll wake up very soon.”

Still, Max-Ernest knew, a coma was a coma. Even if it wasn’t a coma coma. Even if you called it sleep. After all, sleep was not not a coma. Max-Ernest had looked up the word in a dictionary: coma meant “deep sleep” in Greek.

His silence was very frustrating for the people around him. Especially for Cass’s mother and for the doctors and nurses who were trying to figure out what had happened to Cass. Max-Ernest admitted he’d been with Cass when it had happened, but whenever anybody asked him just what exactly it was, he would shrug or look off into the distance.

Without her coming right out and saying so, it was clear Cass’s mom thought he was hiding something. “Why is it Cass is always with you whenever—?” she started to ask at one point, but she didn’t finish her question. “Are you sure you didn’t—?” she started to ask another time, but she didn’t finish that question, either.

She hadn’t wanted to allow Max-Ernest in the hospital room, but Cass’s grandfathers had intervened and reminded her that Max-Ernest was Cass’s best friend.

“Cass would want him here—you know that,” said Grandpa Larry. “And the poor boy feels bad enough as it is—look at him.”

You Have to Stop This

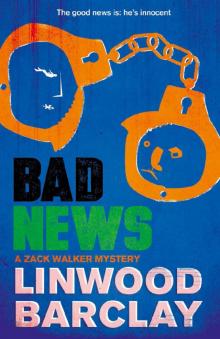

You Have to Stop This Bad News

Bad News Write This Book: A Do-It-Yourself Mystery

Write This Book: A Do-It-Yourself Mystery Bad Magic

Bad Magic If You're Reading This, It's Too Late

If You're Reading This, It's Too Late This Isn't What It Looks Like

This Isn't What It Looks Like Bad Luck

Bad Luck The Name of This Book Is Secret

The Name of This Book Is Secret The Unbelievable Oliver and the Sawed-in-Half Dads

The Unbelievable Oliver and the Sawed-in-Half Dads The Unbelievable Oliver and the Four Jokers

The Unbelievable Oliver and the Four Jokers This Book Is Not Good for You

This Book Is Not Good for You This Isn't What It Looks Like-secret 4

This Isn't What It Looks Like-secret 4 Write This Book: A Do-It-Yourself Mystery (The Secret Series)

Write This Book: A Do-It-Yourself Mystery (The Secret Series)