- Home

- Pseudonymous Bosch

If You're Reading This, It's Too Late

If You're Reading This, It's Too Late Read online

Copyright © 2008 by Pseudonymous Bosch

Illustrations copyright © 2008 by Gilbert Ford

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. (And you thought getting out of P.E. was hard!)

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Visit our Web site at www.HachetteBookGroup.com

First eBook Edition: October 2008

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author. Similarity to persons in a state of half-life, however, is another story.

The Little, Brown and Company name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

ISBN: 978-0-316-04103-4

Contents

Forword

Preface

Chapter 33

Chapter 32

Chapter 31

Chapter 30

Chapter 29

Chapter 28

Chapter 27

Chapter 26

Chapter 25

Chapter 24

Chapter 23

Chapter 22

Chapter 21

Chapter 20

Chapter 19

Chapter 18

Chapter 17

Chapter 16

Chapter 15

Chapter 14

Chapter 13

Chapter 12

Chapter 11

Chapter 10

Chapter 9

Chapter 8

Chapter 7

Chapter 6

Chapter 5

Chapter 4

Chapter 3

Chapter 2

Chapter 1

Appendix

FOR

ENIELEDAM,

SACUL,

AND ILLIL

WITH SPECIAL THANKS TO XWP AHSATAN

FOR LETTING ME STEAL HER SOCK-MONSTER

AUTHOR’S NOTE:

PLEASE READ THE CONTRACT ON THE FOLLOWING PAGE VERY CAREFULLY. IF YOU REFUSE TO SIGN, I’ M AFRAID YOU MUST CLOSE THIS BOOK IMMEDIATELY.

P.B.

The flashlight pierced the darkness

The flashlight slashed through the darkness

The flashlight beam sliced through the darkness like a sword

The flashlight beam darted — yes! — across the dark hall, illuminating a wondrous collection of antique curiosities:

Finely illustrated tarot cards of wizened kings and laughing fools . . . glistening Chinese lacquer boxes concealing spring traps and secret compartments . . . intricately carved cups of wood and ivory designed for making coins and marbles and even fingers disappear . . . shining silver rings that a knowing hand could link and unlink as if they were made of air . . .

A museum of magic.

The circle of light lingered on a luminous crystal ball, as if waiting for some swirling image to appear on the surface. Then it stopped, hesitating on a large bronze lantern — once home, perhaps, to a powerful genie.

Finally, the flashlight beam found its way to a glass display case sitting alone in the middle of the room.

“Ha! At last!” said a woman with a voice like ice.

The man behind the flashlight snickered. “Who was it that said the best place to hide something was in plain sight? What an idiot.” His accent was odd, ominous.

“Just do it!” hissed the woman.

Grasping the heavy flashlight tight in his gloved hand, the man brought it down like an ax. Glass shattered in a cascade, revealing a milky white orb — a giant pearl? — sitting on a bed of black velvet.

Ignoring the sharp, glittering shards, the woman reached with a delicately thin hand — in a delicately thin white glove — and pulled out the orb.

About the size of an ostrich egg, it was translucent and seemed almost to glow from within. The surface had a honeycomb sort of texture comprised of many holes of varying sizes. A thin band of silver circled the orb, dividing it into two equal hemispheres.

The woman pushed aside her white-blonde hair and held the mysterious object to her perfectly shaped ear. As she turned it over, it whispered like an open bottle in the wind.

“I can almost hear him,” she gloated. “That horrid monster!”

“You’re so sure he’s alive? It’s been four, five hundred years . . .”

“A creature like that — so impossible to make — is all the more impossible to kill,” she replied, still listening to the ball in her hand.

A small red bloodstain now marked her white glove where one of the glass shards had cut through; she didn’t seem to notice. “But now he can escape us no longer. The Secret will be mine!”

The flashlight beam fell.

“I mean ours, darling.”

Beneath the shattered display a small brass plaque gleamed. The Sound Prism, origin unknown, it read —

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA AAAAAAAAAAAAARRGH!

I’m sorry — I can’t do it.

I can’t write this book. I’m far too frightened.

Not for myself, you understand. As ruthless as they are, Dr. L and Ms. Mauvais will never find me where I am. (You recognized that insidious duo, didn’t you — by their gloves?*)

No, it’s for you I fear.

I had hoped the contract would protect you, but now that I look the matter square in the face — it’s just not enough.

What if, say, the wrong people saw you reading this book? They might not believe your claims of innocence. That you really know nothing about the Secret.

I regret to say it, but I can’t vouch for what would happen then.

Honestly, I would feel much better writing about something else. Something safer.

Like, say, penguins! Penguins are popular.

No? You don’t want penguins? You want secrets?

Of course you do. Me, too . . . It’s just, well, what if I were to tell you that, after all, I was just the teensiest bit scared? For my own skin, I mean.

Let me put it this way: the monster Ms. Mauvais spoke of — that wasn’t a figure of speech. She meant monster.

So how about giving me a break? Just this once.

What’s that — it’s too late? You signed a contract?

Gee. That’s nice. I thought we had a friendly arrangement, and now you’re threatening me.

Oh, sure. I know how it is. You want to laugh at my jokes. Maybe shed a few tears. But when it comes to having real sympathy for a terrified soul like me — forget it, right?

Readers, you’re all the same. Spoiled, every last one of you. Lying there with your feet up, yelling for someone to bring you more cookies. (Don’t tell me they’re chocolate chip because then I’ll be really mad!)

I’m sorry, I didn’t mean that — this whole writing business is making me crazy.

Let’s be honest — I’m stalling.

In a word: Procrastinating. Putting off. Postponing.

I’m draaaaggggginnnnnnggggg myyyyyy feeeeeet.

You’re right — it’s only going to make my job harder in the end.

Better to jump back in.

Never mind how cold the water is. Or how deep. Or how many man-eating —

The only way to write is to write and I’m just going to —

Wait! I need a second to settle my mind.

Two seconds.

Three.

There. I’m standing on the edge, pen in hand, ready to take the plunge.

&nb

sp; And here I —

HEY, DID YOU JUST

PUSH ME?!?!

WELL, I GUESS IT HAD TO HAPPEN.

BY NOW, WE ALL KNOW I CAN’T KEEP ANYTHING TO MYSELF — NO MATTER HOW DANGEROUS OR ILL-ADVISED.

AND THE TRUTH IS:

Agraveyard at night.

On a mountainside. By a lake.

Our vision is blurred. Rain falls in sheets around us.

Everywhere there is water. Dripping. Dripping.

A strange song starts to play. It sounds far away, yet impossibly close.

Like the singing of fairies or sylphs.

Like the ringing of a thousand tiny voices inside our ears.

Above us, a crow flaps its wings against the rain and, screeching, disappears into the dark.

Lightning briefly illuminates the tombstones at our feet, but they are so old that no trace of name or date remains. They are no longer grave markers; they are just rocks.

What lies beneath is a mystery.

A mouse scurries between the stones, frantic. As if he’s trying to get out of a maze. A deadly trap.

Soon he is joined by others of his kind. They swim against a tide of mud. Clawing at each other in their desperate attempt to escape.

Automatically, we look in the direction they are running from. There is a burial mound with a broken tombstone on top. Its jagged edge silhouetted as lightning strikes a second time.

The strange, eerie song wafts through the wind — until it is drowned out by a crack of thunder.

As we watch, the broken stone topples — and lands with a thud in the mud. A gaping hole is left in the ground. Clods of dirt erupt. A mud volcano.

First one hand, then another — both very, very large — emerge out of the hole, grasping at the mud to find a hold.

And then: a nose.

At least, we think it’s a nose; it could be a cauliflower —

“Cassandra . . . !”

We look down. A lone, stranded mouse is calling to us — as if from a great distance.

“Get up, Cass — it’s late!”

He sounds oddly like our mother —

Shivering, Cass lifted her head off her pillow.

She was a member of a dangerous secret society now, the Terces Society, she reminded herself. Or she would be soon. She couldn’t let a little dream scare her.

What had Pietro, the old magician, said in his letter? That once she and Max-Ernest had sworn the Oath of Terces, they would “face the hazards and the hardships.” And that they must “obey all the orders without the questions.”*

If she couldn’t face her own dreams, how could she face real enemies like Dr. L and Ms. Mauvais? Like the Masters of the Midnight Sun.

Even so, the strange song lingered in her mind, haunting her.

Again.

Each night a different dream. But always the same song.

Why?

“Cassandra!”

Her mother was calling up to her from downstairs. Cass couldn’t hear every word but she knew what her mother was saying:

Get up — it’s late! I’m off to work (. . . or to yoga . . . or to a meeting). There’s oatmeal on the stove (. . . or granola on the counter . . . or a waffle in the toaster). Don’t forget you have your math quiz (. . . or book report . . . or oboe lesson). Love you!

These days, Cass’s mother ended nearly everything she said to Cass with Love you! — kind of like it was a punctuation mark or a nervous tick.

“Love you!”

See.

The front door slammed shut; her mother had left.

Unwilling to get up, Cass stared at the wall facing her bed.

Cass’s Wall of Horrors, her mother called it.

Hundreds of magazine and newspaper clippings covered the wall — all describing disasters, or potential disasters:

Earthquakes. Volcanoes. Tsunamis. Tornadoes.

There were pictures of seabirds blackened by oil spills, and of starving polar bears standing on shrinking icebergs. There were mushroom clouds and poison mushrooms, killer bees and killer mold.

Posters and diagrams showed How to Treat Frostbite . . . The Heimlich Maneuver . . . THREE SIGNS THAT YOU HAVE A THIRD-DEGREE BURN . . . The ABCs of CPR . . .

And in the center of the wall: an article about a bear haunting campers in the mountains. BEAR OR BIGFOOT? the headline read.

Most people — people like Cass’s mother — would find a wall like this very disquieting. Cass found it comforting.

Usually.

As a survivalist, she liked to be prepared for the worst at all times. She could face anything, she felt, if she knew it was coming.

Hurricane? Board up the windows. Drought? Save water. Fire? Don’t panic, avoid smoke inhalation, look for a safe way out.

And yet these were all natural disasters. What would she do, she couldn’t help wondering now, if she ever confronted a supernatural disaster?

That was what upset her about her dreams. They were strange and irrational. They didn’t make sense, as her friend Max-Ernest would say. (Max-Ernest talked compulsively, but he was always very logical.) An earthquake might not be totally predictable but at least it obeyed the laws of nature.

Most of her dreams involved a monstrous creature and a spooky old graveyard. How do you prepare for that?

Not that she thought her dreams were going to come true; she wasn’t superstitious. It was just that they felt so real.

“There must be something in the graveyard you want,” Max-Ernest had said when she finally told him about the dreams. “A dream is the fulfillment of a wish. That’s what Sigmund Freud says. How ’bout that?”*

“But why would I wish for a monster?” Cass had asked. Max-Ernest’s parents were psychologists — so she figured he knew what he was talking about.

“Well, I don’t know if it means you wished for it, exactly. I think dreams are like things you can’t admit you want because you feel guilty or embarrassed or something. It’s called the unconscious,” Max-Ernest had concluded. “It’s kind of confusing.”

Still in bed, Cass thought about what he’d said. She reached under her pillow, pulling out the small stuffed creature she’d hidden beneath it.

“Who are you? What are you?”

Cass’s sock-monster was a little, odd-shaped thing made out of old socks and scraps from her grandfathers’ antiques store. She’d sewn it together in a kind of fever one day, obsessed by the creature from her dreams. It was green and purple and troll-like with a big, sock-heel nose, bulging bottle-cap eyes, and floppy ears made from tennis-shoe tongues. Cass liked the ears especially — ears almost as big but not nearly as pointy as Cass’s own.

Since it was 100 percent recycled, the sock- monster was a super-survivalist, and Cass found that if she held him tight she absorbed his survival powers.

Sometimes.

Other times, he just felt good to hug.*

Maybe, thought Cass, her bad dreams would end when her new life — her secret life, her life with the Terces Society — began.

Like any serious survivalist, Cass followed a rigorous routine every morning:

As soon as she was on her feet, she pulled her backpack out from under her bed and double-checked its contents. The backpack was a custom-made model that Pietro had sent her; it had special secret capabilities, like converting to a tent or a parachute. Even so, Cass kept some of her old survivalist supplies in the backpack — like chewing gum, for its sticking value, and grape juice, which she liked to use as ink.

She didn’t know what her first Terces Society mission would be — all she knew about the society was that it was dedicated to protecting the Secret — but she would be ready.

Next, Cass examined every corner of her house to see if anyone had entered overnight — whether friend or foe.

She checked:

1. The tiny threads of dental floss she tied to the handles of her desk drawers so she’d know if anybody ever opened them.

2. The dried bee corpse she’d discov

ered one day and left strategically on her windowsill.

3. All the windows and mirrors and doors to see whether someone had written a coded message in dust, toothpaste, or shaving cream.

4. And a few other places I won’t give away, in case the wrong person reads this.

Only after she was sure that nothing had changed upstairs did she allow herself to go downstairs, where her first stop was usually the kitchen cupboard. Cass had a hunch she might find the next secret message from the Terces Society in a particular old box of alphabet cereal.

But this morning, when she walked through the kitchen door, Cass let out a very un-survivalist-like gasp of excitement: the magnets on the refrigerator had been moved. They weren’t arranged the way she’d left them the night before (by color rather than letter); she could tell from the doorway.

She covered the distance in two leaps and stood breathless in front of the refrigerator, ready to decipher a coded message or to read directions to a secret meeting place or to take instructions about a new mission. Or all three.

Then her heart sank.

The magnets spelled: LOVE YOU

Clipped underneath was a handwritten note:

7 a.m. Off to work. There’s a waffle — the whole wheat kind — in the toaster. Don’t forget you have your field trip to the tide pools tomorrow — do you know where your windbreaker is? I can’t find it.

M.

M being for Mom or Mother. But also for Mel.

Mel being short for Melanie, her mother’s name.

Hardly a secret code.

Cass crumpled the note in her hand, despondent: why did her mom have to be such a mom?

And when was the Terces Society going to come?

The Xxxxxxxxx School. City of Xxxxx Xxxxxx. Lunchtime.

I’m sorry — I still cannot tell you the name of Cass’s school. Or where the school was located. Or what it looked like. Or almost anything else about it.

Of course, I trust you. But there’s always the possibility that, through no fault of your own, you will toss this book out the window and it will fall into the wrong hands.*

You Have to Stop This

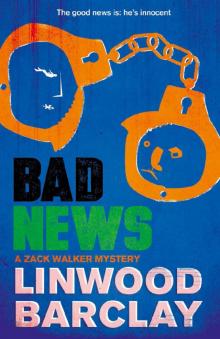

You Have to Stop This Bad News

Bad News Write This Book: A Do-It-Yourself Mystery

Write This Book: A Do-It-Yourself Mystery Bad Magic

Bad Magic If You're Reading This, It's Too Late

If You're Reading This, It's Too Late This Isn't What It Looks Like

This Isn't What It Looks Like Bad Luck

Bad Luck The Name of This Book Is Secret

The Name of This Book Is Secret The Unbelievable Oliver and the Sawed-in-Half Dads

The Unbelievable Oliver and the Sawed-in-Half Dads The Unbelievable Oliver and the Four Jokers

The Unbelievable Oliver and the Four Jokers This Book Is Not Good for You

This Book Is Not Good for You This Isn't What It Looks Like-secret 4

This Isn't What It Looks Like-secret 4 Write This Book: A Do-It-Yourself Mystery (The Secret Series)

Write This Book: A Do-It-Yourself Mystery (The Secret Series)